Like the west-central Wisconsin residents he attended meetings with, Thomas Pearson became aware of frac sand mining as a citizen, concerned about a new industry that threatened to alter lives and landscapes.

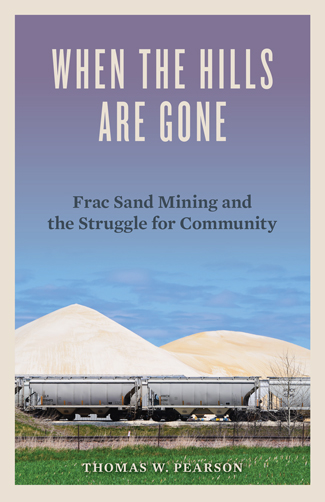

His concern, as he watched the drama unfold, grew into a research project and then, over the course of several years, a book. “When the Hills Are Gone: Frac Sand Mining and the Struggle for Community,” was published in early November by the University of Minnesota Press.

With its title a dead giveaway, the book takes a critical look at the controversial industry and how the corporations behind the mines exerted their influence in the region. None of that is surprising, given that Pearson is an anthropologist and an associate professor of social science at University of Wisconsin-Stout.

With its title a dead giveaway, the book takes a critical look at the controversial industry and how the corporations behind the mines exerted their influence in the region. None of that is surprising, given that Pearson is an anthropologist and an associate professor of social science at University of Wisconsin-Stout.

The 248-page book, however, is more a case study of grass-roots community activism and democratic process than a condemnation of the industry itself, he said, noting that the industry has its supporters too.

“I want people to understand the growing influence of corporate interest and how corrosive that can be for local democracy. A lot of people were caught off guard by frac sand mining. People felt like the mining companies had much more power than they should have,” Pearson said.

“I’m trying not to romanticize grass-roots activism. I’m looking critically too at the circumstances in which grass-roots efforts like these succeed or fail,” he said.

As frac sand mining became a reality throughout west-central Wisconsin starting in 2006 with a rush to open mines on rural land, residents in the affected areas mobilized, if slowly at first.

Pearson was one of them, attending meetings in garages and going to town halls in the lower Chippewa River valley where residents, officials and corporate representatives clashed in cities like Menomonie, Glenwood City, Chippewa Falls and New Auburn and townships like Cooks Valley, Howard, Red Cedar and Tainter.

As of 2016, the region had more than 70 active mines in 13 counties, bounded by Barron and Rusk to the north, Monroe to the south and Wood and Pierce to the east and west. Trempealeau and Chippewa counties have the most, with about a dozen each.

Battle lines in the sand

Residents feared degradation of the landscape and threats to the environment and their health, the latter from silica dust. Sand companies saw profits, jobs, wealth for landowners and claimed that a flattened hill could be turned into farmland, an assertion disputed by activists.

Residents feared degradation of the landscape and threats to the environment and their health, the latter from silica dust. Sand companies saw profits, jobs, wealth for landowners and claimed that a flattened hill could be turned into farmland, an assertion disputed by activists.

Sand mine operations crush prehistoric ridges into sand once again. West-central Wisconsin sand, prized because of its hardness, is mostly transported by rail to oil fields for high-pressure drilling.

Citizen groups like Save Our Hills, Save the Hills Alliance and Loyalty to Our Land fought the process. Notable successes, such as a groundswell effort leading to the rejection of a mine proposed near the Hoffman Hills State Recreation Area in Dunn County, also were met with failures as mines overcame regulatory hurdles, or lack thereof, and opened throughout the region.

One such major proposal by Vista Sand has been on hold for several years. It would include a mine near Glenwood City with a processing plant near Menomonie. The young industry already has experienced boom and bust periods, depending on the oil market.

“For many, frac sand mining presented a sudden threat that drew into question deeply held assumptions about rural landscapes and environmental well-being,” Pearson writes.

“I try to cast a social science light on activism as a phenomenon. A lot of the activism was by people who lived next door and had very little experience at it,” he said, adding that it took several years for established environmental groups to begin supporting residents’ efforts.

“I try to cast a social science light on activism as a phenomenon. A lot of the activism was by people who lived next door and had very little experience at it,” he said, adding that it took several years for established environmental groups to begin supporting residents’ efforts.

He took an on-the-ground approach with his research, essentially embedding himself within the movement, examining why people were opposed and providing firsthand accounts of their efforts.

Pearson, a Chicago native who lives in Menomonie, visited Harlan and Edith Syversen of Dovre. They had sold part of their small dairy farm 10 years earlier to “an aspiring farmer,” who then sold out to a sand company and moved away. Before long, a mine was open a short walk from the Syversens’ once bucolic homestead, which had been in the family for generations.

Part of the book deals with the loss people felt or feared from a landscape being changed forever.

“We inscribe places with meaning, with a sense of history. Mining eliminates, or at least distorts, the cultural script from which that meaning is derived,” Pearson writes.

“When the Hills Are Gone” follows opposition to frac sand mining for about a decade, through 2015. “Hopefully it will offer lessons from the first phase, if and when it becomes a significant issue again,” he said.

Praise and support

Adam Briggle, author of “A Field Philosopher’s Guide to Fracking,” said Pearson’s book is “a masterful blend of stories and scholarship that will be the definitive account of a major environmental justice issue.”

Along with activists from the region, Pearson said he received support in writing the book from colleagues in UW-Stout’s social science department and Center for Applied Ethics; 10 applied social science majors who helped with research via an applied anthropology seminar in fall 2014; undergraduate research assistants; and the university through a Faculty Research Initiative grant.

“When the Hills Are Gone,” paperback, sells for $25 and can be purchased through the University of Minnesota Press. Learn more here.

###

Photos

Top: Thomas Pearson, an anthropologist and associate professor of social science at UW-Stout, has written “When the Hills are Gone: Frac Sand Mining and the Struggle for Community.”

Second: The cover of “When the Hills Are Gone” by UW-Stout’s Thomas Pearson.

Third: Fairmount Minerals operates a sand mine on the east edge of Menomonie. A member of the Young African Leaders Initiative at UW-Stout tours the mine in 2014.

Bottom: Thomas Pearson