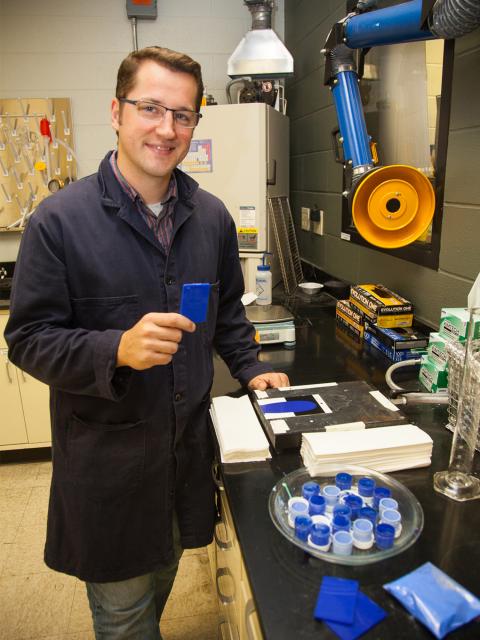

Andrew Smith enjoys color and science, asking questions like, what causes color? How is color formed? How are pigments made? Combining his interests in graduate school at Oregon State University gave him a new perspective.

“I started to understand what color was and how to manipulate it, which was no trivial task. And best of all, it led me into a career where I could research new materials and chart my own path,” he said.

Smith is originally from Minnetonka, Minn. but graduated high school from Cameron, Wis. He earned his bachelor’s in applied science from UW-Stout in 2006. In 2009, he was working as a graduate student in materials chemistry with his adviser, Distinguished Professor Mas Subramanian, and a team at OSU researching multiferroics, materials to be used in electronics.

Smith combined the elements Yttrium, Indium, Manganese and Oxygen and placed the mixture in a furnace at approximately 2,000 degrees. When he removed the composition, typically black or dark gray in color, from the furnace and characterized the hexagonal crystalline structure, he found that it had lost much of its electronic properties. So, he continued to push the compositions.

What Smith removed from the furnace next was a surprise. Instead of black, the new composition was a brilliant blue. Smith had accidentally co-invented a new inorganic pigment.

“My first thought was, ‘Strange. Why would these materials be such a bright blue?’” he said. “I thought that I had contaminated the material or that the ingredients didn't react. When I analyzed the crystal structure, I was surprised to find that I had in fact made a pure material.

“Each composition was a single phase. Think of this like making a proper cake with any ratio of milk and sugar. Yes, the taste may vary, but it still looks and feels like a cake. It was unusual, which was another indication I should find out why. This led to more compositions, analyzing the optical spectra and more crystallography.”

Smith and the team at OSU named their discovery YInMN, for the compounds it contains. Its vibrant blue is not a naturally occurring pigment but instead derives its color from the metallic elements combined with oxygen.

“Andrew is testament to how a hands-on education allows our students to see themselves doing something bigger than they thought they could,” said Ann Parsons, UW-Stout biology professor.

Subramanian, a chemist who had previously worked for DuPont, understood immediately the significance of the team’s discovery. In May 2012, they received a patent with the U.S. Patent Office for the new pigment.

A rare discovery

Blue pigments have appeared in art around the world for thousands of years, as ancient cultures revered the color for its rarity in nature; the first known synthetic blue dates back to ancient Egypt.

YInMN is the first blue pigment discovered in more than 240 years; cobalt was discovered in 1777. New inorganic pigments are rare. In specific color spaces, like blue, they are even more rare, Smith said.

Like cobalt, YInMN’s commercial value stems from its vibrancy and durability. Both pigments are weather resistant and nonfading. However, unlike cobalt, YInMN absorbs ultraviolet energy and reflects infrared wavelengths, acting like a cooling agent, reducing surface temperatures and energy consumption.

“For plastics that are exposed to sunlight, this is a big deal,” Smith explained. “Plastics that overheat can eventually become brittle and degrade, which cause them to lose their color, shape and properties. YInMn can improve the lifetime of the polymer.

“Combining all of that with improved performance over cobalt, one of the most robust inorganic pigments, is impressive.”

In 2015, the Shepherd Color Company, which researches and deals with durable paints and plastics for outdoor uses, acquired the license for commercial sale of YInMN. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency approved the pigment for industrial use in 2017 and approved it for artistic use in 2020.

Commercially known as Blue 01G513, YInMN’s hex triplet – a digital code representing a color – is 2E5090.

Continuation of color research

Smith, who has a master’s in business administration from Xavier University and Ph.D. in materials chemistry from OSU, has been involved with two other patents with the Shepherd Color Company: pyrochlore orange and yellows, and hexagonal magenta, which is an extension of the YInMn chemistry, Smith said.

“My colleague Matt Comstock and I found a way to utilize cobalt to create a vibrant magenta and varying shades of purple,” he said. “We found the material was ideal for glass chemistries as it could be a cheap replacement for purple of Cassius, a gold-based pigment that is used for pigmenting glass in various shades of magenta and red.”

Smith thinks the most fascinating thing about YInMN is not the material itself but the many people around the world who were either inspired by the color, the discovery or the research. It has been featured in TIME Magazine, National Geographic, Bloomberg News and Teen Vogue.

The pigment even inspired a new shade of Crayola crayon, Bluetiful, in 2017.

“I feel as though it renewed the conversation about the importance of color in our lives and provided an opportunity to talk about how advanced color technology is,” he said. “Many of us take it for granted that coloring something like a plastic toy, for example, requires a thorough understanding of color science, polymer chemistry, mathematics and fundamental physics.”

Smith believes UW-Stout gave him a solid foundation for succeeding as a researcher and as operations manager for Winchester Interconnect in Peabody, Mass. As a “color enthusiast,” he also serves on the advisory board for the Pigment and Color Science Forum.

“I was inspired by professors that encouraged me to think freely, pushed me into new areas of research and challenged my understanding of science and technology,” he said. “They were instrumental in my development as a scientist.”

During his undergrad, Smith was asked by now Professor Emeritus Chuck Bomar to intern as part of a Gilbert Creek restorative project. Smith chose to intern at OSU in an estuary study instead, opening the door to his entrance at OSU.

“The nature of being curious is one Andrew’s strong suits,” Bomar said. “He understands that learning is a lifelong process. He’s curious and asks questions. He likes to try new things and he’s not afraid to screw up. He exemplifies what it means to be a Stout student.”

The applied science program offers concentrations in applied physics, biology, industrial chemistry, interdisciplinary science, and materials and nanoscience. It also offers a prehealth track to prepare students for medical school and other health care fields.