In a hall packed with student researchers stood a team of engineering students led by Sam Gibbs, of Eau Claire, demonstrating their solution to a civic issue an ocean away. Across the corridor, graduating senior Gwendolyn Olson, of Manitowoc, shared her knowledge of one of the world’s most famous scientists and artists.

They joined more than 300 UW-Stout students who exhibited almost 120 research projects at the STEMM Student Expo on Dec. 8, in the Memorial Student Center. The expo is an annual showcase of student projects, including prototype development, solving industry or community problems, lab research or a creative activity completed as part of a course.

It is an opportunity for first-year to senior students across the College of Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics and Management to collaborate on projects and discuss their research with each other, faculty, industry partners and university and community members.

Finding solutions for global waste management issues

Gibbs, a second-year computer and electrical engineering student, developed a Garbage Collection Notification System with a team of four other students. They researched the recent waste management issues in Govan, a community in Glasgow, Scotland.

He developed a device for optimizing waste collection with:

- Lewis Cargeor, a first-year mechanical engineering student, Minneapolis

- Ryan Crotteau, a first-year engineering technology student, Eau Claire

- Alessandro DeLisio, a senior in engineering technology, North Hollywood, Calif.

- Sam Mars, a first-year manufacturing engineering student, Menomonie

Their project was based on an Engineers Without Borders case study which named several civic challenges and opportunities for improvement identified by the residents of Govan, including waste management. About 50 projects at the expo were based on the Engineers Without Borders case project and various community needs.

The issues in Govan were brought on by strained financial resources, a shortage of waste management professionals, limited recycling and an influx in the population, as refugees from around the world are relocated there, Gibbs explained. Reduced public waste collection has led to issues of uncleanliness, rats, swarms of flies and improper disposal with risks of pollution.

The city has placed QR codes on 5,000 public waste collection bins for residents to scan and report full, damaged or overflowing bins. The scan sends an alert to waste management companies.

“But people aren’t scanning the codes, and management isn’t being notified. The result is excess trash in the city streets,” Gibbs explained.

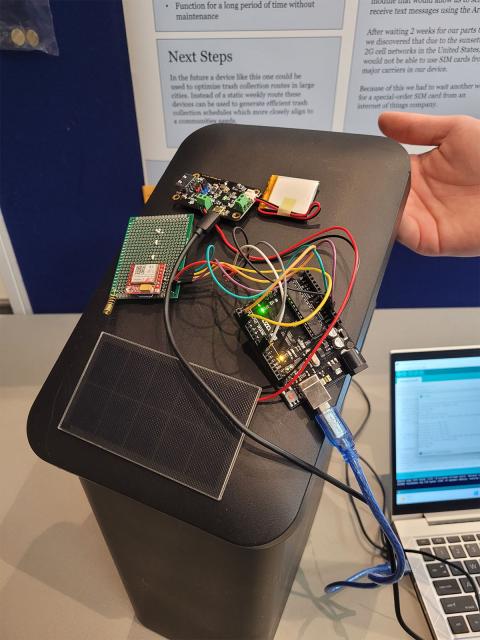

The team’s automated, cost-efficient device is a sensor placed in bins that monitors the level of trash within and alerts management of the locations of the bins that need to be emptied, optimizing collection routes.

“The sensors are solar powered; otherwise they can run for 72 hours off the battery. The cost to produce the sensor was $47, and if this project were to go into production, that cost would fall dramatically,” Gibbs explained.

Overcoming the rift between science and religion

Olson, a senior in food science and technology, presented her research on “Leonardo Da Vinci: The Rift Between Science and Religion.” Olson believes that in today's society, there are many rifts in the scientific realm.

“I think that some science is becoming what the people want to hear due to politics and social media. This is much like the religious rift Da Vinci dealt with,” she said. “The only real difference is instead of being told the wrong answers, we purposely frame an answer or conduct studies we know will give particular answers. This issue arises with funding for projects by investors looking for a specific outcome or commercials that attach phrases like ‘scientifically proven’ to a product.”

She completed her research as part of Professor Marcia Miller-Rodeberg’s Advanced Biochemistry course. About 12 students displayed their research on scientists who made major contributions to science and society and who are also classified as a minority or underprivileged.

“The importance of this research is to bring a small piece of history and diversity into a science class,” said Miller-Rodeberg, who encourages students to participate in the expo “because it gives them an opportunity to present their research, potentially for the first time, in a comfortable setting. It is great practice for students to present their work both orally and written.”

Olson chose to research Da Vinci because “people tend to think of science as studies and research, but I find it interesting to understand how today's knowledge differs from that of the past.

“My favorite part of this assignment was learning that Da Vinci didn't have anything. He came from a broken household with no education and no real last name,” she explained. “Yet in a time where you were born into your status and the church established all scientific beliefs, he was able to start the research and theories we use across all areas of science, including physics, evolution, biology and astronomy. I think it truly shows everyone has the ability to be more than where they came from.”

Olson believes the rift between science and religion needs to be overcome. “But it will take the understanding that not all studies will produce the desired results. Even if results are undesirable to media, politics or industry, they still need to be published so people can better educate themselves.”

She also exhibited research on “Fermentation of Wine Increases Production of Gallic Acid” as part of an independent study. This was her second year participating in the expo. “I enjoy it. I learned many interesting things and enjoyed the science behind so many of the projects there,” she said.

Olson will graduate on Saturday, Dec. 17. She plans to earn her master's in microbiology or immunology and work part time doing lab testing in a hospital. Her goal is to work with the Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to create cures and antitoxins for food-borne illnesses and infections.